“Hiatus”: that awkward, ominous word every devoted music fan fears might mean the end of their favourite band. Though a hiatus isn’t nearly as traumatic as an actual breakup, one can never be too sure when it comes to musicians.

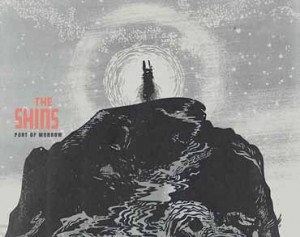

Many feared that the five-year departure taken by frontman James Mercer would mean the end of the Shins. The last time we heard from the likes of Mercer was in the form of Broken Bells, a marriage between his own dreamy musings and Danger Mouse’s fine-tuned, radio-ready production. Through this brief departure, Mercer—who had long avoided the influence of producers—realized his own potential for bigger, more vibrant songwriting. It’s no surprise, then, that some of this seems to have rubbed off on his first love, and it’s safe to assume that Port of Morrow marks a new era for this band.

Then again, “band” is sort of a relative term when it comes to the Shins. These days, “the Shins” is really just another way of saying “James Mercer and friends”; Mercer has been quoted expressing an interest in being an auteur, à la Billy Corgan, and seems to have followed through with this intention. The rest of the band is now a completely different group from what Zach Braff first heard when Natalie Portman eagerly handed him her headphones over all those years ago in Garden State, and one might wonder, after listening to Port of Morrow, whether we can really continue to call them the Shins. The slow, reflective nature of Mercer’s brainchild has evolved into a sunny, uptempo, and occasionally danceable affair, flirting with power pop. One may have been able to spend a solitary afternoon daydreaming and listening to Oh, Inverted World or Wincing the Night Away, but Port of Morrow lends itself perfectly to sing-alongs in car rides on sunny afternoons with a row of friends in the back seat. What would Braff make of this transformation?

If there’s a word to describe this album, it’s “reassuring”. Mercer’s lyrics are sung with the voice of someone who has made it to the other side and has life’s mysteries mostly figured out. The songwriting lacks much of the subtlety of Mercer’s earlier work, which is not to say it’s a step backward; some of the most irresistibly catchy stuff of the Shins’ career can be found here without the sacrifice of lyrical profundity.

“The Rifle’s Spiral” kicks off the pack with a skipping beat, swirling instrumentation, and a high-flying vocal melody with a steady upward momentum. It invokes the feeling of embarking off on an adventure, which indeed we are. “Simple Song” begins with a cheery march, building dramatically to a triumphant chorus and setting the optimistic tone of the album. “It’s Only Life” dials the energy back with an affectionate letter to a friend, and we begin to remember what it was we liked so much about this band in the first place.

The last two songs feel like love letters from present-day Mercer to his 20-something self, assuring him that living isn’t nearly as tough as it seems at first. “September” is probably the closest thing this album has to a classic Shins song, and it’s a welcome change of pace, but it benefits from standing alone in that. The energy continues to pick up and wind down all the way to the end of the album, ultimately ending with an ethereal title track that sends the listener peacefully to sleep after an enjoyable reunion with a high school bestie, now a little older, a little wiser, but somehow more fun than the last time you hung out.

So is it safe to call this a definitive Shins album? I guess that depends on how you define “band” to begin with. the Shins of yesteryear dealt with the perplexities and inherent tribulations of life, while the Shins of today are all for going outside and living it despite them. This the kind of record that everyone needs to hear, because when it really comes down to it, we all need to learn to do that as well as the Shins have.

MMM½